With almost a quarter century of the new millennium behind us, we have an opportune time to reflect upon the international system that has defined this new period. The decades between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the present day bore witness to several important and unprecedented military interventions that give shape and structure to this new world order. Perhaps the most pivotal of these episodes was the United States-led attack on Yugoslavia in the last months of the twentieth century. Last summer marked the 75th anniversary of NATO, with a big bash in Washington that signaled the military alliance’s full embrace of a new mission with no pretensions to modesty or respect for the sovereignty and autonomy of other nations. Seventy-five years on, NATO’s mission is no longer, if it ever was, a defensive one. Today, NATO wears its higher imperial ambitions on its sleeve, openly issuing provocations to other global and regional powers and expanding its sphere of influence far beyond its founding mission. This new mission is consistent with the actions undertaken by NATO since the end of the Soviet Union: in this period, the imperialism of the U.S. becomes increasingly self-referential and self-justificatory, its rules-based order defined by the words of Thrasymachus in Plato’s Republic: “Justice is the advantage of the strongest.” International bodies have since adopted a posture of deference toward the decisions and actions of the United States government. Because there is no institution capable of checking the US in practice, the legal and institutional paradigm must be flexible enough to accommodate the criminal aggression of the United States.

In NATO’s founding era, “ideological litmus testing was wholly absent,” with the U.S. and its allies embracing authoritarian dictatorships no less than supposed liberal democracies. But in the post-Soviet era, liberal-democratic ideology comes to the fore, providing a new basis for aggressive warfare, emphasizing the importance of supporting “young” and “struggling” democracies in Europe, as Bill Clinton’s address in March 1999 underscored. Having outlasted its original raison d’etre, NATO perversely became its own institutional end, one that had very little to do with Europe’s security. The new NATO mission took on a deeply ideological quality, a commitment to arrogating the power to act as adjudicator of conflict and safeguard of global security:

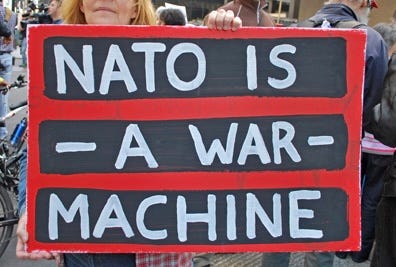

A recent paper from the Institute for Peace & Diplomacy’s Christopher Mott contends that NATO “has shed its defensive basis and been reconceived as an organization whose primary directive is to expand America’s sphere of influence globally through the continuous encroachment on various regional powers’ more immediate spheres of interest.” NATO has become one of the primary mechanisms through which the United States government imposes its political and economic will, a way to recreate and strengthen a capitalist imperial order, “subordinating the strategic autonomy of NATO’s relatively powerful members to Washington’s priorities.” The novel innovation of the Clinton Doctrine was its willingness to punish the innocent as a means of expressing indignation at the guilty. Many continue to wonder whether Western indignation should suffice as a rationale for the upending of international law and the destruction of another nation’s people, right to self-determination, infrastructure, and economy, particularly in light of the fact that the U.S. has been the major cause of human rights violations in the world for at least a century.

Yugoslavia served as a test of the still very new and developing post-Soviet system, one in which the United States had no real rivals. In Washington, the prevailing belief was that within this new context, any substantive, enforceable limits on the power of the United States government could only undermine the standing of human rights and democracy in the world. We end up with the paradoxical and self-contradictory position of the United States that global peace and security could be imposed through aggressive war and violence, that it must be so imposed. In theory, the rules-based order to which America’s ruling class spends so much time referring requires certain conditions to be met before a sovereign nation can be invaded militarily, most important among them, the explicit authorization from the UN Security Council. The NATO alliance chose to ignore the demands of the law in favor of a nebulous mix of standards. NATO’s illegal military response to the situation in Yugoslavia raises important questions about the meaning of inviolable state sovereignty and territorial integrity in the post-Westphalian world, bringing these ideas into apparent conflict with human rights. The ability to subordinate the ostensibly equal sovereignty of another state to concepts provided by human rights signals a return to the pre-Westphalian paradigm or, more precisely, the development of a new supranational form of sovereignty in which the U.S. can suspend the international order, creating new exceptions for itself unilaterally. This unilateralism has become the modus operandi of the U.S. As astute observers have pointed out, this approach inverts the proper structure of international law as something outside of and above any particular state. It makes the United Nations impotent, a tool of the United States and the NATO military bloc. International law is emptied of its substantive law in favor of the cynical ratification of whatever the actions of the United States and its allies happen to be.

The question of how NATO came by the incredible prerogative to dictate terms to a sovereign state was the uncomfortable elephant in the room for the West on the question of Yugoslavia. As Peter Schwarz wrote at the time in the scholarly journal Peace Research, “The negotiations [in Rambouillet, France] were first supposed to deal with the question of Kosovar autonomy, and only then take up the question of the military measures to be implemented to carry this out. This was the basis for the Yugoslav government participating in the conference.” Leading the negotiations for NATO was a small contact group made up of the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Italy. There was little doubt at the time, even among many of the leaders of NATO allies, that Yugoslavia had been drawn into a perilous bait-and-switch, given an ultimatum that it could neither accept nor reject. A widely noted episode on the NATO ambush bears repeating here. An “unimpeachable press source” traveling with then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright reported of the boasts of one senior State Department official, who stated that the United States had “deliberately set the bar higher than the Serbs could accept.” The terms of the agreement are incomprehensible except as a transparent attemptto convince skeptics that a NATO raid was unavoidable.

Yugoslavia was, without its assent, dragged into a process of negotiating away its own security; it was then given a document whose terms would violate Yugoslav sovereignty and let NATO run roughshod over its lands. This was an open and obvious trap. The naked cynicism with which NATO conducted itself during the “negotiations” at Rambouillet eroded trust in the alliance, which thereafter becomes increasingly associated with attempts to spread and consolidate the geopolitical ambitions of the United States and its allies. NATO began its bombing campaign against Yugoslavia in the final week of March 1999, after negotiations conducted over the previous two months failed to produce the West’s desired result, which included the arbitrary and unprecedented demand that the NATO military bloc be permitted to occupy without restriction the territory of Yugoslavia, a sovereign country. Under the pretext of maintaining peace, NATO presented a position that gave it unlimited free rein in Yugoslavia:

NATO personnel shall enjoy, together with their vehicles, vessels, aircraft, and equipment, free and unrestricted passage and unimpeded access throughout the FRY [Yugoslavia] including associated airspace and territorial waters. This shall include, but not be limited to, the right of bivouac, maneuver, billet, and utilization of any areas or facilities as required for support, training, and operations.

This demand provides context and demonstrates that fundamentally NATO does not believe it should deign to negotiate with less militarily powerful actors, their sovereignty as inscribed in international law notwithstanding. Given the circumstances, it would have been political malpractice of the most serious kind for a head of state to accept these terms; the result of acceding would have been a NATO occupation without any limits or safeguards, which means that Yugoslavia had no reason to accept the “deal” on the table. It was an impressive achievement in subterfuge: the rules give the appearance of objectivity and respect for well-established principles of international law. But in practice, the standards applied give way to the interests at play, and the rules are interpreted in self-serving and motivated ways. The extremeness and unconscionability of the NATO position presented at Rambouillet drew heavy criticism, even from those inclined to accept unjustified, aggressive military actions. No less a war-hawk than Henry Kissinger damned the NATO military action as violating longstanding principles of international law in violating territorial sovereignty. The test of human rights is both over and under-defined. One of the few consensus opinions within the community of nations is that there is no shortage of human rights violations in the world. All nations believe that their enemies are violating human rights, and all nations are quite correct in this belief. But the human rights standard itself does not act in the world, mediated as it is through interpretation and adjudication. While many (and, importantly, both supporters and of the attacks on Yugoslavia) acknowledged violations within Yugoslavia’s borders, the UN Security Council declined to permit NATO’s use of force.

In the post-war period, NATO becomes one of the key drivers of the growth in the power and political influence of the military-industrial complex of which Eisenhower so famously warned. NATO expansion has been attended by a steady growth in global arms production and transfer, at the center of which are American war profiteers closely tied to policymakers and the national security bureaucracy. Recent scholarship has noted that, in Europe today, “the military-industrial complex is arguably transforming into a complex with a noteworthy commercial civilian dimension,” expanding the national security sphere beyond the “traditional military.” That is, the top-to-bottom military ordering of life has succeeded in colonizing and co-opting much of the social and political order. For decades, industrial and political power have coalesced around the massive gravity well of public-private partnerships in the areas of military technology, organization, and governance. This is consistent with the broader trend of state capitalism in which the formal distinction between the state and the corporate economy has given way and faded in the practical reality of open and direct collusion between the two. This tendency is always immanent in capitalism, in its history and ideological paradigms, for the state created the power of capital itself, its first and last role being the extension of authoritarian state power. Today, NATO operates through a “highly bureaucratic and top-down structure” at the pinnacle of which are positioned the interests of the United States; members that attempt to structure their own foreign affairs through agreements outside of U.S.-prescribed and approved channels are subject to “intense disapprobation,”

NATO expanded quickly in the years following the end of the Soviet Union. From its original 12 members, NATO has since added 20 additional members in successive waves, beginning in the early ‘50s and running to the present, for the 32 member states of today’s alliance. Between the fall of the Berlin Wall and today, NATO has added 16 states, with major accession groups in the first years of the new millennium. Declassified documentshave since shown beyond peradventure that these successive territorial expansions of NATO came in direct contradiction to explicit promises made by top U.S. government officials. “The documents reinforce former CIA Director Robert Gates’s criticism of ‘pressing ahead with expansion of NATO eastward [in the 1990s], when Gorbachev and others were led to believe that wouldn’t happen.’ The key phrase, buttressed by the documents, is ‘led to believe.’” As NATO expands in an era characterized by largely unquestioned American political and economic hegemony, the ideological content carried by the military bloc becomes more apparent and prominent. Thus has it become possible for the liberal or progressive half of our political class to lead the charge for American cultural and political hegemony and empire in the twenty-first century. “For most of the last century, the Democrats have been the world’s foremost imperialist political party.” In a post-Cold War, end-of-history global setting, Western liberals saw an open and irrevocable invitation, indeed mandate, to spread the American system—hard military power transmogrified into benign peace-keeping and service to human rights. In making the promulgation of American-style neoliberalism the paramount goal of Washington’s foreign affairs, the American political center, perhaps especially liberals, have been able to reconcile with imperialism. The identitarian character of U.S. hegemony has cloaked its more fundamental class character, the purpose it serves within the overall system of production.

It is more than a little ironic that the defenders of Western “liberal democratic” empire should be so critical of the teleologies they find in socialism. The rhetoric of empire in the United States both before and after the demise of the Soviet Union is pointedly and specifically teleological in its character: history is unfolding in a particular direction, with a specific purpose, propelled by the superiority of the American way, by its inevitability. This worldview establishes stages of history in a way strikingly similar to the one Western liberals have long criticized. It posits a highly specific and stylized story about history and its fundamental features and functions. This account of history serves the goals of the empire by giving the U.S. and its allies permission to help underdeveloped countries move into the new, better world order. Their sovereignty, if we can speak of it, is contingent on the adoption of specific political and economic policies and social practices. The new universals being posited by the narrative of history (Western-style “free markets” meaning cheap nature, exploitation, and resource extraction; highly mediated representative “democracy” with an extremely powerful and unaccountable central government serving finance capital; etc.) are inescapable and must be taken up. The ticket into recognition is acceptance of the universal vision and its ideas about development and progress. Within the context of so-called humanitarian intervention, this liberal teleology insists that the conceptual inviolability of states’ sovereign borders remains that—conceptual only. It provides a one-sided story that ignores or underplays the material interests of the parties arguing for military intervention, fixing the pretextual reasons in the public imagination as the only reasons.

Over 500 innocents and about 1,000 members of Yugoslavia’s security forces were killed in the illegal campaign, according to a report from Human Rights Watch. While it ultimately (and unsurprisingly) declined to recommend prosecution for violations of international law, the committee’s final report, completed in May 2000, noted that NATO’s replies to its investigation were inadequate and “failed to address the specific incidents” of which UN members complained. It is hardly coincidence that in its discretion and decisions on which countries are ripe for destruction and regime change, the focus of the United States is on “developing” nations that are not at parity with it either economically or militarily. Yugoslavia helped to create an international system in which “illegal but justified” U.S. interventions “are met with minimal rebuke in recognition of the mitigating circumstances.” If NATO’s military attack on a sovereign country was permissible, then surely so were the “soft power,” economic campaigns it was waging throughout the world. The United States’ economic strangulation projects (for example, in Haiti and Iraq) through brutal sanctions policies intended to starve innocent people “were the equivalents of the bombing of the Serb infrastructure.” The legacy of NATO aggression in Yugoslavia has loomed large in contemporary global affairs. The U.S.-led invasion of Libya, beginning in 2011 during the Obama administration, was a similarly clear instance of the U.S. and its allies flouting international law in order to accomplish a regime-change operation. As Curtis Doebbler, a legal scholar and expert on international law, noted at the time, “[Western nations] went to great pains to claim that the use of force against Libya was legal, but an application of international law to the facts indicates that in fact the use of force is illegal.” Once the new standard had been established, the merits of projects like regime change in Libya were judged not by cognizable standards of international law, but by cost-benefit analyses in Washington. Yugoslavia signaled the United States’ readiness to reinvigorate old philosophical and rhetorical strategies for legitimating its imperial and colonial projects. It is of a piece with U.S. efforts to subdue and extract from the Global South in that it specifically relies on notions of developmentality. In the twentieth century, the violence and brutality of Europe’s colonial projects came home to roost in the emergence of fascism and Nazism; we have not yet come to terms with “how colonization works to decivilize the colonizer, to brutalize him in the true sense of the word, to degrade him, to awaken him to buried instincts, to covetousness, violence, race hatred, and moral relativism.” In American political discourses, there is no place for any close consideration of the necessary relationship between the imperial project of repression and extraction and a domestic politics defined by nationalism, bigotry, and misogyny. “The development of the Western world, secured by its global counterrevolution, is the mirror image of Third-World misery.” In the American imagination, NATO is the benign alliance of the West’s free countries. It is a shield against the backwardness and authoritarianism of the rest of the world, an Avengers-style team of liberal democracies. But today, NATO’s role in America’s domestic politics is to obscure the imperial efforts and attendant violations of international law, and to cover this aggression in the veneer of moral rectitude and respect for human rights.

This is one of the clearest postmortems I’ve read on the NATO shift from postwar alliance to post-legal enforcement mechanism. You’ve traced the ideological mutation from “collective defense” to “imperial prerogative” with both moral weight and archival rigor. The Rambouillet section especially deserves wider attention—rarely do these documents re-enter the discourse with such clarity.

What we’d love to see next—from you or others—is the companion question: What now?

If the imperial compact is sustained by self-justifying liberal teleology, and the legal structures (UN, ICC, sovereignty norms) have all buckled under U.S. exceptionism, then what does real sovereignty look like now?

You’ve dismantled the myth of benevolent empire. What remains is the opportunity—maybe even the obligation—to imagine how governance gets rebuilt in its absence. Not abstractly. Not globally. But at ground level: towns, networks, oaths, jurisdictions. That’s the work we’re trying to take up from a different angle.

In solidarity,

—The Radical Federalist