The rate of language loss today is higher than it has ever been in recorded history. The data from the past several decades reveal that hundreds of languages were lost in those years, and that the rate of loss has accelerated over time and continues to do so today. Researchers estimate that more than 43% of the world’s approximately 7,100 languages are already endangered (some place this value as high as >50%), and they could be looking at extinction by the end of this century if current trends hold. In fact, available data suggest an overwhelming and tragic truth: “On average, every month across the globe, two Indigenous languages disappear, according to the United Nations. And 40% of the world’s languages, mostly Indigenous, are threatened with long-term extinction as fewer and fewer people speak them.” The world is losing something of indescribable and immeasurable social and cultural importance, and we never hear about it.

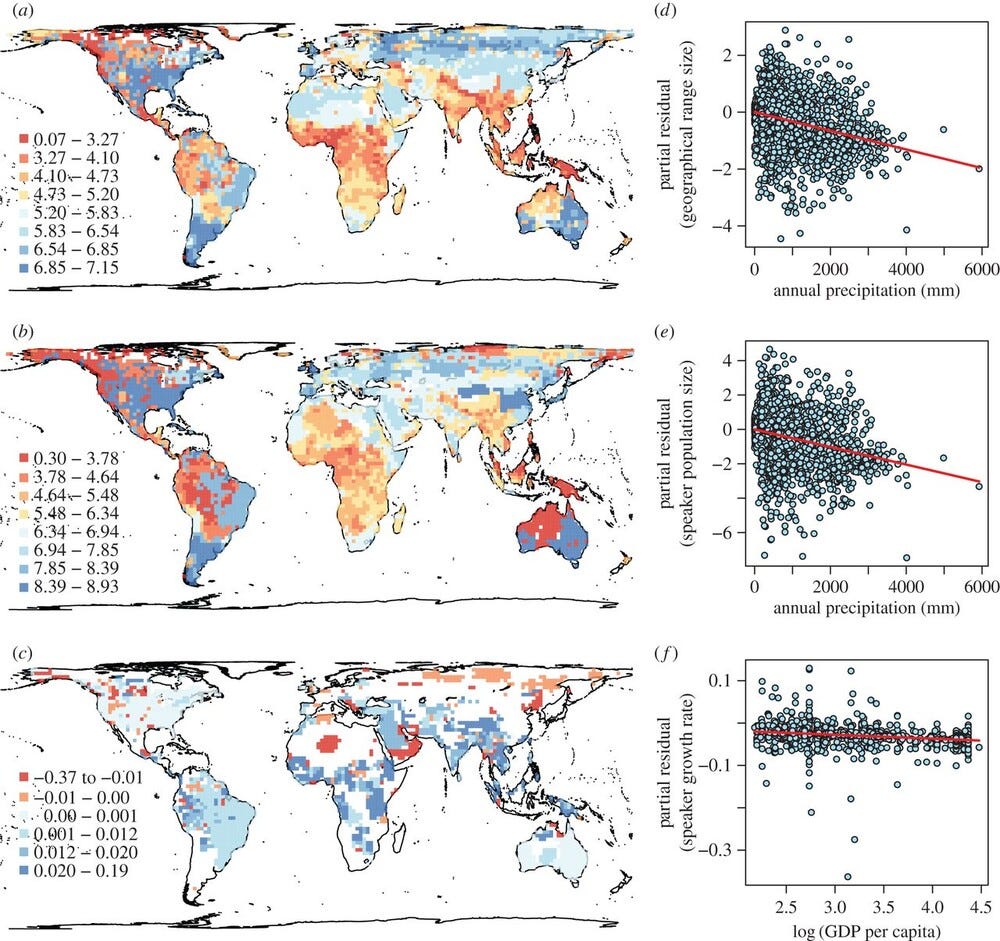

It is never just language that it lost, though this would be bad enough. The loss of a language is also the loss of unique cultural practices, oral traditions and myths, and specialized knowledge of the environment, etc., that may not obtain anywhere else on the planet. There is something deeply defective about our cultural values when we are allowing this to pass basically unremarked on. In an effort to better assess the impacts of language loss across the planet and regionally, researchers have used a measure, “functional richness,” similar to one used in ecology, indicating the number of unique species occupying a particular niche space in an area; this interdisciplinary idea underscores the fact that language diversity isn’t strictly cultural. It is critically also tightly intertwined with ecological knowledge and thus our real-world adaptation to environments. The destruction and death of languages parallels environmental degradation and niche ecosystem loss, with massive ramifications for both sustainability and cultural heritage. We can’t afford to see the language extinction crisis in isolated or one-dimensional terms. Researchers have been able to identify several global regions in which the impacts of language loss are particularly acutely felt, Northeast South America, Oregon and Alaska, and northern Australia: “Regions where all Indigenous language are endangered — including parts of South America and the United States — face the greatest consequences.” This research has shown that the degree of variation across languages is higher than was previously thought, offering new insights into language evolution.

We still have not been able to bring ourselves to look directly at this crisis: “More than race or religion, language is a window on to the deepest levels of human diversity. The familiar map of the world’s 200 or so nation-states is superficial compared with the little-known map of its 7,000 languages.” The extinction of languages dramatically undermines cultural diversity, as spoken language is among the core vessels of social identity and knowledge for any community of people. The death of a language means the loss of unique ways of seeing and relating to the world and understanding nature, fundamental reality, and history, all of which is always embedded in language from its structure to its words. Philosophers and linguists have long theorized that the languages we speak shape the structure and content of our thoughts and ways of life, that our modes of language give the structure to our social reality as human beings. No doubt it would be wrong to make claims of certainty about how this system works causally or about the degree to which it is one of many factors giving substance to social reality. What is more clear is that language is one of the most important and sacred aspects of our inheritance as human beings.

A world with fewer languages is a world with fewer ideas. The loss of language necessarily narrows the cognitive and cultural horizons of our species, making us more vulnerable to dreaded uniformity of thought and thus to authoritarianism. My hypothesis is that maintaining a rich diversity of languages safeguards a wide range of conceptual repertoires, categories, and metaphors. And when we have a broad base of such diverse systems, they function as cross-checks against reductionist or propagandistic thinking and narratives. Losing languages means reducing available cognitive antibodies. I think this is part of what we are watching unfold today. As different as the teams think they are (and they are surely meaningfully different in some ways, though nowhere close to as different as most think), both have bear-hug embraced the same unbelievably impoverished and enshittified system of thought and culture. Maybe people dress differently, or some people go to church and some don’t. But everyone accepts the steady enshittification of everything, the toxicity and insanity of the smartphone culture, the selling out and abandonment of the next generation, the necessity of police statism and authoritarianism in some shape, etc. What is needed is to remove the air from that system, to withdraw attention and reverence, to get along with the business of doing things in a different way.

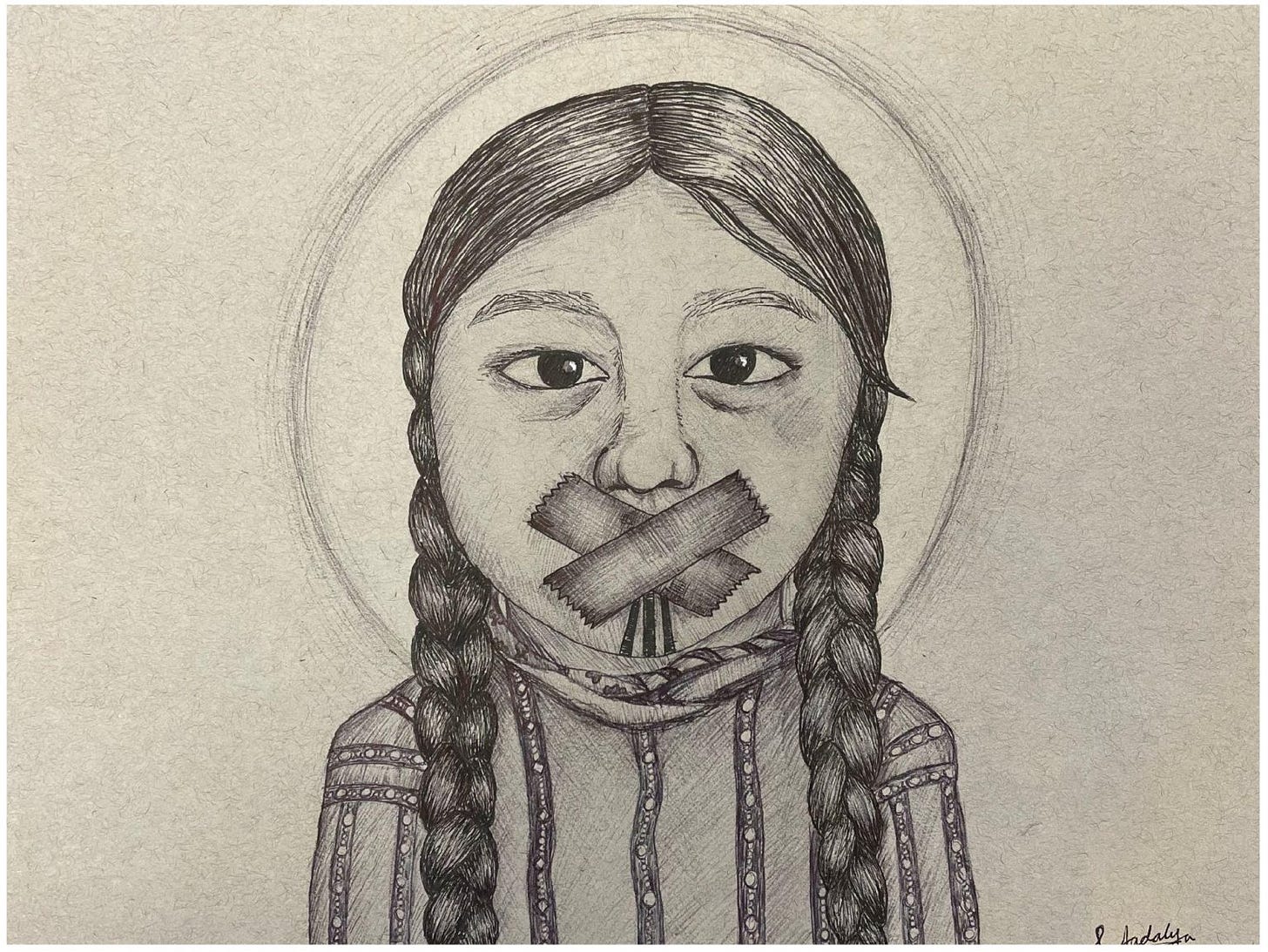

The fact that the crisis of language loss remains almost completely unaddressed points to a more general cultural failure to understand the immeasurable value of diversity beyond commercial or pecuniary interests (I suppose this thought makes one overly sentimental in the hyper-vulgar, post-values twenty-first century). We have to learn to see this issue in terms of cultural impoverishment, to appreciate that we are losing something we can never recover, narrowing humanity’s collective heritage and thus its future. In accepting the language extinction crisis, we are limiting the adaptive potential of the human species. The version of globalization we have—an unlimited-consumption culture that relies on stealing from the global south—promotes cultural and linguistic homogenization and marginalizes indigenous and minority languages. I don’t think we can any longer afford to see such dynamics as neutral or inevitable. To erase a language is always to erase a culture and history. In light of the history of colonialism and racial oppression, fighting to protect language diversity is an inherently political act, contesting hegemonic power and reclaiming agency over cultural futures.

The communication of concepts is impossible without language, so our concepts always depend to a certain degree on the words we use to represent them. Different languages are thus always creating and operating within different conceptual frameworks, though we can get close to a 1:1 relationship if we isolate single words (we might, for example, think that sí and yes represent exactly the same thing). But as soon as we pile up the words and delve into more difficult or complex philosophical territory, perfect translation and 1:1 equation become impossible. Different languages make different ideas visible; as I’ve discussed elsewhere, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of linguistic relativity claims that different languages divide up and organize the world in distinct ways, providing some of the shape to how their speakers perceive reality and fundamental truth:

This fact is very significant for modern science, for it means that no individual is free to describe nature with absolute impartiality but is constrained to certain modes of interpretation even while he thinks himself most free. The person most nearly free in such respects would be a linguist familiar with very many widely different linguistic systems. As yet no linguist is in any such position. We are thus introduced to a new principle of relativity, which holds that all observers are not led by the same physical evidence to the same picture of the universe, unless their linguistic backgrounds are similar, or can in some way be calibrated.

Even if the strongest versions of the linguistic relativity claim aren’t strictly true as some iron law, I think the idea can help us understand why talking about the language extinction crisis is so important. As Benjamin Lee Whorf himself puts it:

We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages. The categories and types that we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find there because they stare every observer in the face; on the contrary, the world is presented in a kaleidoscopic flux of impressions which has to be organized by our minds—and this means largely by the linguistic systems in our minds.

In a sense, it is almost trivially true that language influences the way we think. It is clear, for instance, that we are more likely to remember things if we pay more attention to them. Different languages distribute emphases and draw attention to different things, with differing inherent attitudes toward everything from science and time to gender and ethnic differences. One popular example highlights differences in the ways that speakers of English and Mandarin picture the passage of time. In English, we tend to see and describe time and its passage in terms of a horizontal line; typically, as we move into the future, English speakers think of ourselves as moving rightward along the line. In the Mandarin language, it is common for speakers to think about time in terms of a vertical line, where one descends downward as they move into the future. Researchers have conducted experiments in attempts to understand the practical importance of such linguistic differences on the ways we think. These studies show that English speakers have an easier time answering questions about time if the context they’re given is their familiar left-right dimension. Researchers observed the same of speakers of Mandarin Chinese when they are using the vertical metaphor. “What this suggests is that sociolinguistic conventions impact where, in space, temporal constructs are deemed to reside.” We might also say that language diversity reveals otherwise invisible details, perhaps like different wavelengths make visible more of the electromagnetic spectrum. Losing language diversity is losing access to these distinctive cognitive pathways, limiting the intellectual potential of human futures. Among the strongest arguments in favor of fighting to preserve what is left of our language heritage is the insurance that diversity offers against total uniformity of thought and way of life. If a language comes with a picture or account of reality, then language loss extinguishes whole universes of thought. We lose collectively and subject ourselves to unnecessary danger when we pretend that one dimension of thought or language holds the key to the truth. We have to ask whether we want a blinkered future, a landscape of ideas totally dominated by those of a small ruling class.

We are moving quickly and steadily in the direction of that future, the one we know from George Orwell, where the narrowing of language has narrowed thought (and vice versa). As Nineteen Eighty-Four teaches, authoritarian regimes exploit language itself to cow and manipulate us. Serious, dialectical libertarians must see this unfolding and intensifying language crisis as a serious threat to global political and economic freedom. It is important for people today to understand that the advent of the modern nation-state is linked historically and intrinsically to a decline in linguistic diversity. Modern governments have strongly and systematically promoted language homogeneity to consolidate power and forge a collective identity, violently suppressing minority languages. The authoritarian approach that has characterized the modern state expressed itself through official language dictates, discriminatory political and economic practices, and oppressive educational systems. Increasingly, language standardization elevated a particular dialect, that of the most powerful class, as the most formal and prestigious one, devaluing now non-standard varieties and minority languages and associating them with low social position and backwardness. From a historical perspective, the same processes used by emerging European nation-states to cement internal unity were then applied externally to their colonies.

If we had not allowed our capacity for critical thinking to rot out, we would see immediately that our entire political-economic system and way of talking about it is a highly refined form of doublespeak. We routinely use the language of liberalism, democracy, constitutionally-limited government, and competitive markets to describe a lawless, authoritarian system of police statism and monopoly capitalism. We have lost the ability to describe the social, political and economic world as it is, capable only of describing it within the limited vocabulary the ruling class gives us, like the proles in Nineteen Eighty-Four. This is among the many reasons libertarianism, and really now I speak of right-libertarianism, is one of the most interesting and productive points of departure for discussing and criticizing our politics as Americans. The problems with right-libertarianism are those of American politics generally. In the era of Donald Trump’s Republican Party, right-libertarianism is almost beyond caricature, but it is still a mistake to see the glaring contradictions of right-libertarianism as mere hypocrisy. They are the symptoms of a political and economic system. I have long believed that starting from these contradictions permits us to interrogate the American political system at its ideological core. This example, right-wing libertarianism, shows something about political language and George Orwell’s thesis. It shows how something can mean both itself and its opposite at the same time. Much of the pro-capitalist and right-libertarian rhetoric functions in a layered way in that the terms themselves (for example, freedom, small or limited government, competition, etc.) operate in two directions at once; they operate at the register of their stated meaning, where libertarianism is about legitimate individual rights, an economic system with a level playing field, and a generally open and free society.

But the rhetoric also operates to deflect valid criticism of the overall social, political and economic environment. In this register, freedom is used cynically to excuse, for example, the domination and surveillance imposed by corporations; small government can mean a Pentagon that spends $1 trillion per year, with militarized and hypertrophic police forces domestically; free competition can mean state-favored and -supported global monopolies. We have a situation in which the signifier, freedom or liberty, is real and valid, retaining the power to mobilize commitment and political energy. But the practical institutional effect of freedom within this political-economic context and constructed in this way is its own negation. The terms are applied in confused and hypocritical ways, no doubt, but it is more than that. Because under the capitalist system, words like freedom are structurally double (carrying both the aspiration and its inversion), they are analytically useful and powerful. They give us a way to study how our politics sustains itself through this auto-antonymic mode, whereby concepts are hollowed out and repurposed, but they still carry their original emotional charge. The treatment of the Constitution itself on the political right is another good example of this: it is worshipped as a symbol, not respected as what it is, so its symbolic energy can’t ever really function as a constraint on power. The American right isn’t really defending the Constitution as much as it is commodifying it as a brand or a fetish. Is freedom genuine liberty from arbitrary interference or the freedom of the capitalists to dominate and exploit? Is competition a system of many entrants, relatively evenly matched or a system of powerful, state-favored monopolists? Does small government mean real limits on the power of the state and the reaches of its coercion or the endless expansion of the most coercive and repressive features of the state? But it really makes no sense to see this merely in terms of hypocrisy at the level of the individual person. What we observe is a systematic upshot of the whole structure, a property that is there on purpose because of its important function. The ideological system requires terms that are capable of performing both of the roles at the same time. This is a way that the ruling class can keep us focused on the political shouting match, where everyone claims faithful adherence to the cherished ideals, while reproducing the opposite of the stated ideals. The cessation of this process of control is only possible if it is understood and addressed directly. The parties can be swapped out or switch places with each other and nothing will change unless we see the mechanism. This is not new or unique to the current political moment, but is a structural design feature of the system imposed by the state and capital working together. The state and capital reproduce themselves ideologically by making their legitimacy hinge on ideals like freedom, equality, and competition that end up enacted as their opposites, domination, hierarchy, monopoly, etc.

Addressing the language loss crisis is so important because if we are already this confused in our own political culture and language, we might worry about what happens if we lose even more languages. Orwell’s book may be a realistic picture of the future. If we’re trapped in contradictory meanings even within American political parlance, further narrowing the spectrum of linguistic diversity could be catastrophic. The confusion itself is not the only danger. As the number of languages falls, ideological control consolidates, and the ruling class can dictate both the meanings and their opposites without encountering real resistance. I think that’s where we are in the U.S. now across our political culture. Languages like English, connected with political and economic power, have become dominant in the world of law, international business, and diplomacy. This has created a class system under which people proficient in the dominant, ruling-class language have a powerful advantage, further incentivizing the abandonment of non-dominant languages. A report published by UNESCO in 2022 pointed out that less than 2 percent of the world’s languages have a significant presence online. “You do the math,” says Stanford University historian Thomas Mullaney: “That’s an extremely long tail of languages being left behind.” So as the internet has become an ever more indispensable aspect of contemporary life for education, banking, business, communication, etc., this pervasive lack of representation will further marginalize and strangle languages already at risk. Arguably language has moved from identity to commodity, some scholars now observing a shift in how language is understood and valued. It has gone from a marker of ethno-national identity to an economic resource and resume item under global monopoly capitalism.

Today’s anti-authoritarians should extend traditional concepts of alienation and commodification to the analysis of language loss, arguing that under capitalism, language skills and even multilingualism itself have become commodities to be harnessed and exploited by capital. This warped, alienated relationship to language has led, for example, to the alienation of indigenous peoples from their own linguistic heritage. Today, the utility and labor associated with language skills, particularly in English and other centers of economic power, are increasingly treated as purchaseable, marketable assets in the global system. This dynamic obviously has profound implications for the ways we use language, conceive of identity and subjectivity, and confront social inequality. I believe that the effort to preserve endangered languages is an act of intellectual rebellion against authoritarian forces that seek to narrow human thought. I also believe that the concern about language loss goes to Orwell’s points about the need for clarity in language and writing. A robust cultural ecosystem with multiple languages, each with its own way of dissecting nature, confronts us constantly with the fact that our own worldview is not the only one. This linguistic variety forces us to grapple with different conceptual frameworks and normative systems, perhaps requiring or giving rise to a certain clarity of thought. This is the kind of clarity Orwell was talking about.

Beautiful ❤️