The size and complexity of human institutions has grown tremendously in comparatively very recent history, first during what’s called the Neolithic Revolution, then again in the transition into the industrial era. If violent rulership was invented during the former, then it found its perfect form in the latter, and the information age—in which we’ve become perfectly knowable as a series of identification numbers and data points—has further refined this total control to the point where virtually everything we do is known, and measured, and leveraged for the gain of a faraway elite. Noting “the powerlessness of the individual and the small face-to-face group in the world today,” Colin Ward remarked that they are weak due to their own surrender, their own negligent, thoughtless, unimaginative willingness to cede power to the state. How uncomfortable it is to be told the truth—that we are to blame. And how distressing, if energizing, it is to know that the social order might have been different and may yet be different.

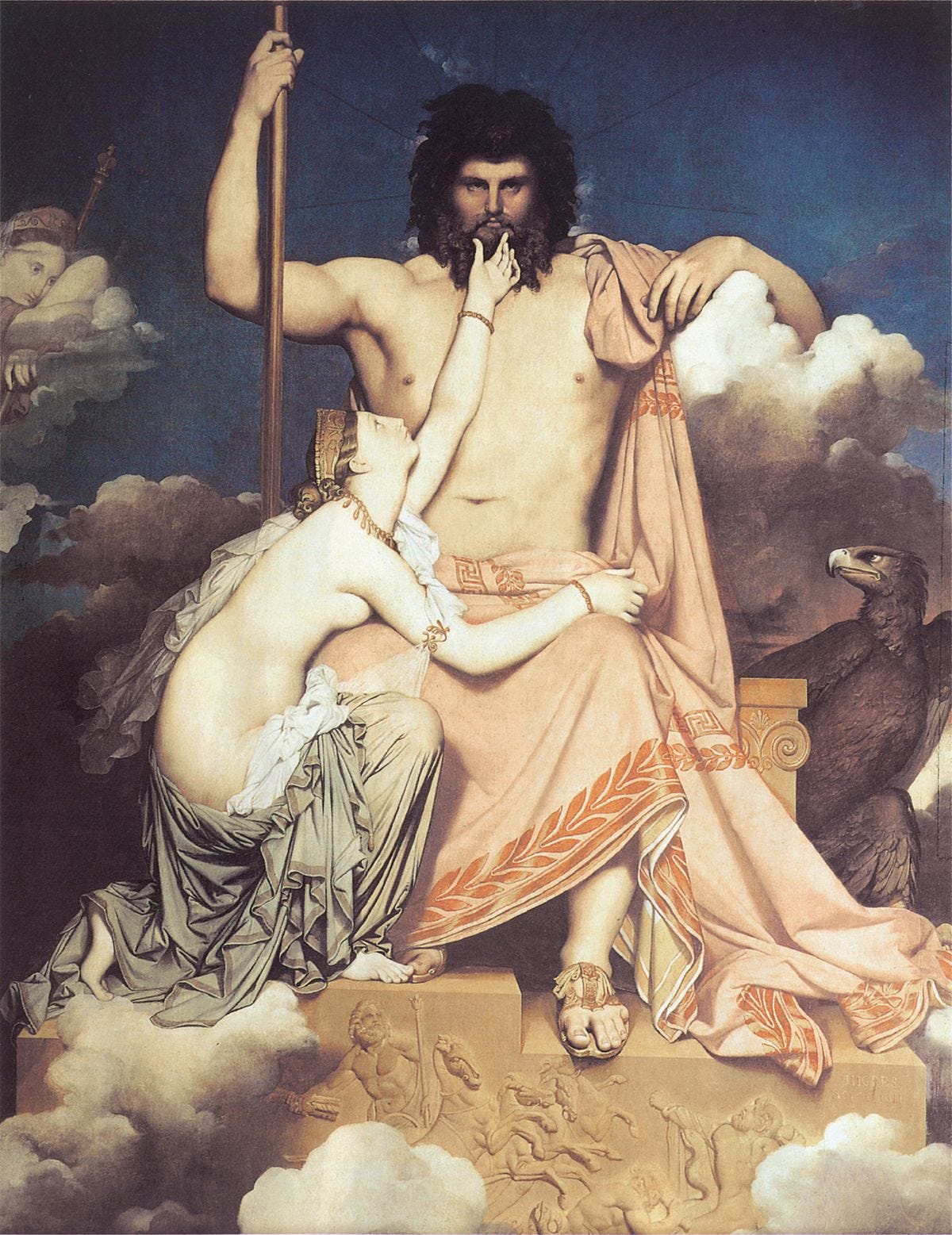

We’ve proceeded as a species into a period of history when we are able to test what seem to be the outermost limits of an interesting question: as within gigantic institutions ruled by a distant elite, how distant is too distant? How deep does an asymmetry of power have to be before it is too deep, too dangerous to human life and the future thereof? The answer from our elites imparts our new marching orders and our new religion, a religion not so different from the polytheistic ones that dominated the earliest civilizations and replaced the animism of thousands of generations of our blood—which we may see not so much as a religion in the sense of rules and prohibitions, but as an attentive awareness of the interconnectedness, impermanence, and interdependence of all things. Pre-historic animism was a natural, meditative response to nature and the mystery of life, where the new polytheisms were a clear, if not deliberate, attempt to buttress a system of violent class stratification. We see their reflections today: the new religion is corporate capitalism, its gods company slogans and logos, its rituals performance reviews and productivity measures. People are only people insofar as they are productive (with productivity defined in a specific way) and sufficiently loyal to these slogans and logos. As in other, earlier polytheisms, all these owe their fealty to a king of the gods, a Jovian figure, here the ultimate corporate monopoly and the source of all others, the modern state. It is important to recall here that the modern state was born as a profit-driven corporation, as a successor to and reorganization of a feudal class system in which “government” was the private organization of landed warlords and senior church leaders. As some earlier transitions had reallocated power from emperors and king to barons and lords, so did the transition to the Westphalian state apportion power to an ascendant elite in the secular corporate world. We needn’t caricature the state. It is enough to show that it was organized first as a stakeholders’ steering committee of landowners, emerging capitalists, and other socially and politically important families. This is just what the state was and remains. Its whole reason for being is to redistribute wealth upward to this committee and its hangers-on, not to promote the common good, or the rule of law, or justice or égalité. The purpose of the state was to renegotiate an existing system of class rule to make it more palatable and sustainable, staving off violent revolutions that could seriously or permanently disrupt the upward redistribution of wealth that has always characterized sedentary human civilization (contrary to the claims of conservatives since time beyond memory or record).

This is another area in which the strange and recent left-right paradigm falls short of its mission: those who know the story of the modern age could never separate the power of the modern nation-state from that of the modern corporation; the two are as closely connected as any social phenomena in human history (and prehistory). As a historical fact, the modern state, which was a group of actual people in power, created the modern corporation as a way to monopolize emerging global commerce for the benefit of a coterie of socially and economically influential elites, these elites occupying positions of importance both in the political and economic worlds. Why should it be any different?

The question our leaders dare not confront is whether we could have changed so quickly—to go, on a dime, in evolutionary terms, from foraging in bands of a few hundreds to arranging in globe-spanning hierarchies in which almost no one has a meaningful role to play in the decision-making processes that affect her life. Confronting the question would require these leaders to question the sources and foundations of their power and wealth, a tall order for mere mortals. Better to accept the rationalizations of their forebears than to scrutinize power structures of which they are the beneficiaries.

The scale and complexity of our state and corporate institutions has grown incredibly quickly, such that we are today totally anonymous to our rulers. Scholars continue to debate the population of the Roman Empire at its height, but perhaps it was 70 million. It’s possible that this number represented about a third of the human population at that time. But nothing like today’s impersonal distances and dizzyingly steep hierarchies ruled the Empire as a matter of fact. In point of fact, ambitions in the direction of the kinds of centralization and hierarchy we see today were the destruction of Rome. The turn-of-the-century scholar Bernard Holland put it best when he observed that it was not “over-greatness” that killed Rome, but “over-centralization,” the death of the provinces in favor of the metropolis. Today, we see this all around us: the people are detached from the land, from a sense of meaning and purpose, told to obey and work for a wage, not humans but automatons, surviving rather than living. Perhaps this will be fine when the transition is complete, when computer intelligence has replaced the human animal, but for now, the result is alienation, shame, and exploitation. The great George Woodcock was characteristically prescient on this subject:

For these reasons the anarchist proposes, as the necessary basis for any transformation of society, the breaking down of the gigantic impersonal structures of the State and of the great corporations that dominate industry and communications. Instead of attempting to concentrate social functions on the largest possible scales, which progressively increases the distance between the individual and the source of responsibility even in modern democracies, we should begin again from the smallest practicable unit of organization, so that face-to-face contacts can take the place of remote commands, and everyone involved in an operation can not only know how and why it is going on, but can also share directly in decisions regarding anything that affects him directly, either as a worker or as a citizen.

In case the relevance of this principle of subsidiarity, the emphasis on “the smallest practicable unit,” is not immediately apparent, it is an attempt to respect the complexity of human beings and the peculiarities of our local knowledge. As the Institute for Peace & Diplomacy’s Christopher Mott recently observed, there is a “tendency to reduce local complexity in exchange for a grand, universal, teleological narrative that ends with, you know, the rapture, or the end of history, or whatever you want to call it.” Such narratives are uniquely modern; there is a single, overwhelming truth in the direction of which we are all moving, without hope of resisting—and, in any case, why resist? The obliteration of difference and individuality will be sublime. We know where it’s all heading (if only because we read Orwell and Huxley in middle school), but, consistent with Ward’s observation, we find ourselves unable to imagine any response but total, shameful surrender. Such shame is the natural antecedent of social alienation, causing us to shrink from each other and thus from the kind of shared awareness of our shame that would be revolutionary. Our shame, to paraphrase Marx, contains the germ of revolution, but only insofar as we become conscious of it and activated by it.

Whether it will someday be possible to maintain the traditional form of accountability as first-hand knowledge and face-to-face interactions, is a question now much less about our technological capabilities than about our will and imagination. As contemporary anarchist writer Kevin A. Carson has argued, we must articulate new ideas of progress and growth that don’t simply amount to ever-larger and more centralized institutions. If we can’t muster this kind of imagination, it won’t be over-greatness that destroys us, but over-centralization, the increasingly concentrated control of the few over the many, the acceleration of the means of this control, the metastasizing belief that this control isn’t just natural (no one cares what that means anyway) but inevitable.