Upon accepting the Right LivelihoodAward in 1983, Leopold Kohr warned that both left and right were “hopelessly leading in the same direction: the abyss of unmanageable proportions.” A scholar of human scale living and self-described philosophical anarchist, Kohr was as far-seeing as any writer in his diagnosis of the cult of bigness. For Kohr, the solution to humanity’s most pressing issues lay in the direction “of a small-scale social environment,” of resistance to the extension of centralized control and of positive efforts toward “decontrolling locally centred and nourished communities.” Accepting the Award he said, “[T]he real problem of our time is not material but dimensional. It is one of scale, one of proportions, one of size, not a problem of any particular kind.” Kohr’s insight here is critical: humans of the Anthropocene are and will continue to be beset by the same problems we have always faced—sickness, poverty, hunger, war, etc. Today, however, the vastness of the institutions that make up the global order puts civilization constantly on the edge of toppling. We are engaged in a game whose rules oblige the maximization of short-term profit, the costs to be paid by a future we won’t live to see.

With such proportions comes the problem of proximity, what Kohr, following Raul Prebish, calls the Law of Peripheral Neglect. Libertarians and anarchists of all kinds know it well, even if not by name; given vaster distances separating a specific problem from the political authority ruling over an area, that authority becomes more likely to discount or overlook the problem. Human beings evolved to look after what is close to them, close both in concrete, physical terms and in emotional and psychological terms. Today’s major institutions, whether formally owned by governments or the so-called private sector, are the same in their gigantic size, their unknowable bureaucracy, their anonymity, their remoteness. Such institutional features do not and could not possibly work for social animals whose evolutionary history finds them in small, intimate groups in which anonymity and free-riding were not aspects of social reality. Unsurprisingly, there is “a rich body of research showing a link between anonymity and abusive behavior.” Researchers have “found that the larger the size of the group, the higher the degree of anonymity experienced by the group’s members, hence stronger antisocial behavior.” Anything shared by a large population of people who are nameless, faceless strangers to one another will fall into waste and disrepair; if the shared thing is a corporate entity (again, whether nominally public or private), its survival must come to depend on theft, exploitation, and the systematic elimination of both direct competitors and naturally available alternatives.

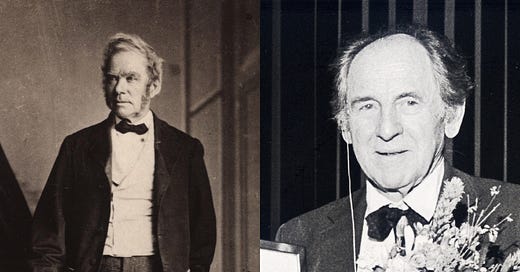

The libertarian polymath Josiah Warren long ago understood the nature of the problem, proposing a workable way forward that would allow people to harness the many benefits of market competition and exchange without abusing one another and devastating the natural world. Warren set forth a libertarian system of “equitable commerce” defined by fair, non-exploitative exchanges in an environment without the kind of systematic coercion that creates great disparities of bargaining power. Over a century ago, Warren’s biographer, the anarchist writer William Bailie, described Warren’s ideas thusly:

Every one should be free to dispose of his person, his time, his property, and his reputation as he pleases. But always at his own cost. Note it well. This is the core of Warren’s principle, the element of justice in it, the basis of equality, the seed of an eternal truth which can no more be refuted to-day than when he first enunciated it to an unheeding world.

Capitalism is defined by its lack of appreciation for the responsibility variable in this calculus, the duty one has to internalize her costs to the best of her ability. As we shouldn’t use other people as means to our ends, neither should we use the property of others or, importantly, unowned property for our own private ends. The liberty aspect of the formula unbalanced by the responsibility aspect ultimately means unchecked, exploitative license, the extraction of value without compensation. It is clear that capitalism is not a free market of the kind imagined and practiced by Josiah Warren. Capitalism, whatever else it is, seems to be about a competition in which the winner has maximized the amount of harm redirected to the commons—that is, one who has stolen something of value from the commons.

The prevailing system precludes, as indeed it must in order to exist, appropriate compensation for the overflowing harms associated with its operation. The destruction of shared environments and the overconsumption of shared natural resources are decidedly not reflected in the prices consumers see at the point of sale. The entire system collapses as soon as final prices begin to reflect the enormous costs associated with such a pace of mechanized production and mindless overconsumption. Global capitalism is a system out of balance precisely because it has as its goal maximum advantage-taking of the people and places least able to effectively protect themselves. Such a system really has nothing to do with the worthwhile ideals of voluntary exchange, or supply and demand, or comparative advantage, etc. Something like an economic system of free markets would have to incorporate Warren’s core element of justice, the equitable upper limit on growth. Today’s political and economic religion of growth for the sake of growth can recognize no such limits, for the idea of both producing less and consuming less is anathema to contemporary modes of philosophy.

It is the mistake of today’s libertarians, principled and well-meaning though they may be, to defend capitalism and the cult of GDP growth. It is the mistake of today’s left, no less well-meaning, to defend the hyper-centralizing cult of the modern nation-state. And as with the near-pointless left-right dichotomy,

the state vs. market (or public vs. private) paradigm is far from the most useful one when considering human institutions. Market libertarians must begin to treat multinational corporations as what they are: the rent-seeking creations of coercive, exploitative state power, not the results of a robust, bottom-up, polycentric order. A decentralist, anarchist approach to the governance of shared resources should iterate on the trailblazing work of Elinor Ostrom, “shifting from positing simple systems to using more complex frameworks.” Ostrom’s work counsels a conscious abandonment of our strained and outmoded modernist models, the capitalist market and the nation-state. As a practical matter, human beings cooperating and communicating in small groups of genuine stakeholders have devised a diverse range of governance structures that are not recognizably either standard market or government structures. Ostrom’s empirical approach demonstrated once more that “isolated, anonymous individuals overharvest from common-pool resources.” She showed that the real-life users of such resources, holding invaluable knowledge of local conditions and special circumstances, could overcome this problem—and outperform governments.

Now, with all of its eggs in one basket, humanity’s familiar pattern of misdeeds and miscalculations represents a threat of a very unfamiliar kind—that is, an existential threat. We can no longer find any civilization that is completely isolated from the rest of the world, a truly remarkable fact the implications of which are appreciated by almost no one today. The very oldest people alive today were born in the twentieth century, and by even its first half, planet earth was a globally connected place, home to billions of people. To truly understand this is to understand that we live in an age that is materially different from just about all of human history. Humanity’s very recent fixation with behemoth planet-spanning institutions is utterly without precedent in our history. That such institutions don’t work for us or serve human happiness is a fact so hideous and obtrusive that it should go without saying. The notion that these institutions are rational or efficient is laughably absurd, as they must be, at fairly regular intervals, propped up and bailed out, saved from what they are and from the crises they engender. As Kirkpatrick Sale writes in the 2017 edition of Human Scale,

[The] truth is that now, well into the twenty-first century, particularly in advanced industrial countries, the world is enduring a series of plights and predicaments beyond any yet experienced in the procession of civilized societies (emphasis in original).

But we need not abolish our institutional Titans; rather, through a federalistic approach, they must be made manageable and comprehensible, evolving from their present “unsurveyable dimensions.” Though we cannot hope now to return to a world without a globe-straddling single civilization, we may yet find a way to an appropriate and sustainable balance between the local and the global.