My Own Little Labadie Collection

Opposed to this are the libertarians, if indeed there are any, who do not presume to tell anybody how to live, provided they will allow the next fellow to also live his life as he sees fit. The genuine libertarian is not bent on establishing ends or prescribing laws, but has been searching for a method of societal life which is dynamic, which allows variety, change, mutability, and realizes that real education is a matter of trial and error and experience and requires, as a genuinely scientific organization requires, complete Liberty and Anarchy, as opposed to the static hamstringing and imposition of coercion and violence by the State.

-Laurance Labadie

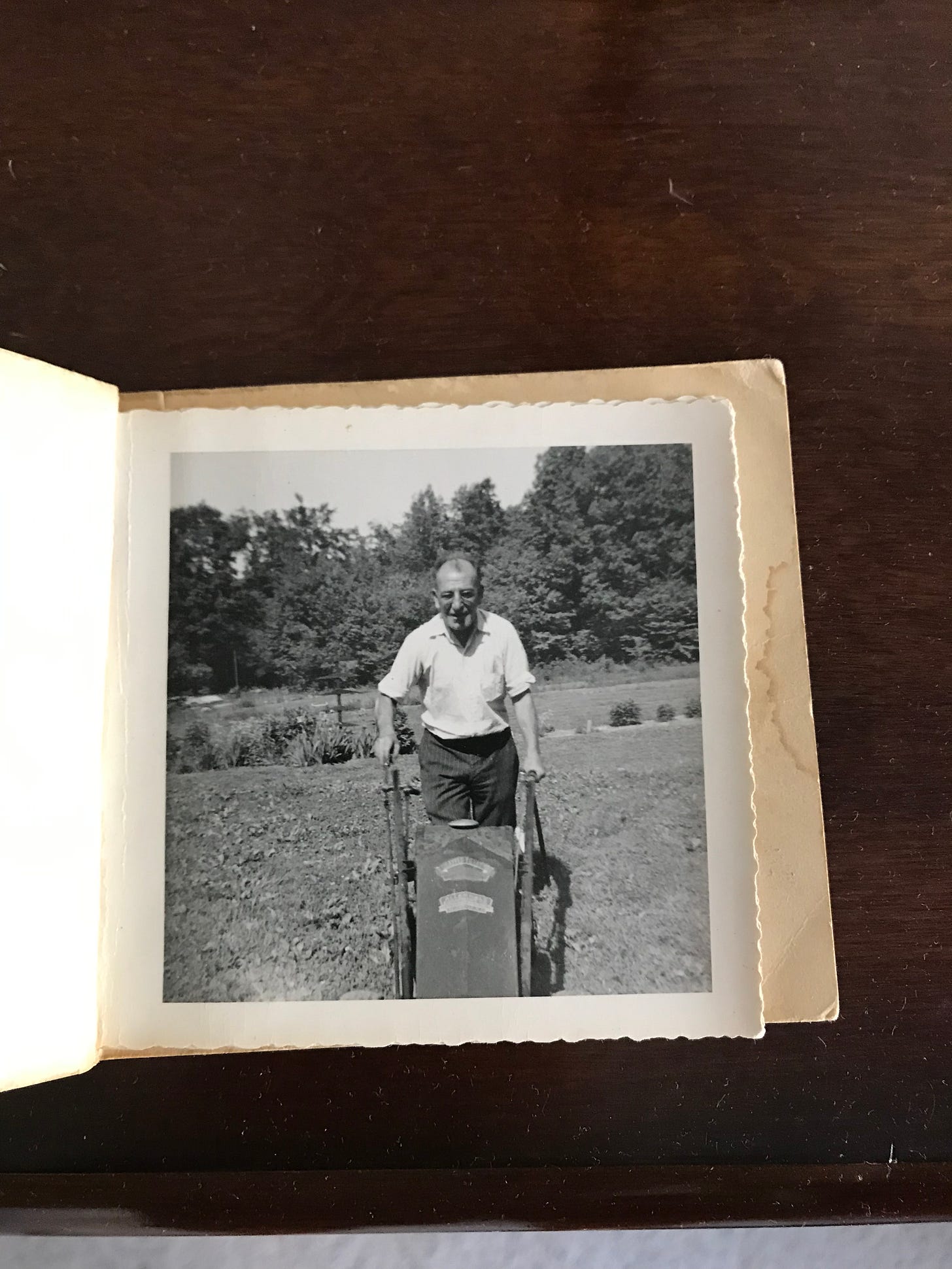

Several years ago, good fortune brought me into contact with one Mr. Ken Ricci, a personal friend of the anarchist writer Laurance Labadie, the son of Joseph Labadie. To my care, Mr. Ricci generously entrusted some papers and photographs that he received following the death of Laurance Labadie. Mr. Ricci’s was a humbling and most appreciated gift; it made me feel more closely connected not only to the Labadies, both of whom continue to inspire me, but to the history of a homegrown American anarchist culture and community that has meant so much to me. Holding these letters, poems, and photographs feels personal, confronting me with the fuller reality of these luminaries of American anarchism as actual people. And Laurance Labadie’s life in particular represents to me another, more important confrontation—that between the individualist anarchism he inherited from Tucker and the distinctive, decentralist homesteading philosophy of Ralph Borsodi and his School of Living.

As Mark A. Sullivan observes, “Labadie took a melancholy delight in discovering and exposing” the “curious contradictions in the structure of our authoritarian society.” Though he “concluded, toward the end of his life, that he had had no influence whatever,” Laurance Labadie has had a lasting influence on me and the way I think about people and our attempts at society. Very much like Labadie, I’ve felt acutely the fact of having been “thrust into a world saturated with the institutionalized imbecilities of [my] ancestors,” unable to make much sense of those imbecilities or of what human beings have been up to since we arrived on the scene. Labadie seems to have understood the deep insanity of our species much better than most of today’s happy optimists in the chattering classes, who are too self-impressed and absorbed in perpetuating the teachings of humanity’s various death cults to consider a more studied view of what we really are. More specifically, Labadie could not swallow the derisive children’s story that human history consists of the steady, more-or-less linear march of civilization and progress. Labadie regarded as hopeless the expectation of anything “other than the eventual extinction of men,” and he believed that few people have ever had an original idea, instead simply going along to get along in “this degenerating and putrescent society.” Pessimism doesn’t sell, particularly to those who haven’t thought very deeply about very much, and so the name Laurance Labadie regrettably remains a marginal one in an already marginal movement within a movement.

Laurance Labadie was, in the words of historian James J. Martin, “the last direct link to Benjamin R. Tucker,” which, perhaps, means more than it says. Labadie was among the last living specimens of a species of anarchist that is all but extinct, the individualist variety associated with, among other focal points of activism and thought, Angela and Ezra Heywood’s The Word, The New England Labor Reform League, and, most famously, Tucker’s periodical Liberty (1881-1908). The anarchist movement has changed much since the Liberty era, though it must be said that individualist anarchism was a unique and separate phenomenon even then—and quite self-consciously so. After all, Benjamin R. Tucker fits neither turn-of-the-century nor contemporary stereotypes of the radical left-winger, much less the anarchist. But where Tucker’s ill fit owed perhaps to his upbringing and milieu—that of a bourgeois Massachusetts gentleman—Labadie stands out among anarchists for his unqualified hatred of “reformers and do-gooders of all varieties,” especially the various schools of communists, socialists, and collectivists. And this, again, places him on a branch (twig, maybe) of the radical family tree that is almost dead, that of the anti-capitalist free marketeer. Yet, as compared with Labadie’s lifetime, we may today be in the middle of an individualist anarchist revival of sorts, the internet allowing curious libertarians access to priceless treasures such as Shawn Wilbur’s Liberty archive, brought to the web from John Zube’s microfiche collection. As the memory of Laurance Labadie and his work likewise deserve to live on, I’ll continue to share here the gems I received from Mr. Ricci.