Capitalist accumulation tends not only toward a progressively deeper class division between labor and capital but also toward increasing concentration and centralization of the power to dispose over capital as it expands.

Paul Mattick

The state and capital have, quite together, managed to hollow out true society, the kinds of community organizations (often volunteer-run, informal, controlled by neither government nor capitalists) that create a vibrant and diverse social ecosystem and collective culture. Without this intermediate social sphere, the popular masses become even more politically and economically atrophied and dependent, losing the strength and know-how to organize and bring out liberatory change. Perhaps the local, the tangible, and the practical can’t ever truly match the splendor of the state, with its stirring songs and symbols. And this may give us a plausible explanation of why it is that people continue to invest in the state (emotionally and in every other way) and to see it as an anchor of community, despite its history of mass murder and hateful disregard for human life. The modern state is far and away the most dangerous human institution in the history of civilization. From a historical standpoint, we are living during a time when the state and capital have aligned in their efforts to constrain and undermine society’s intermediate, local or community-level bodies. They have pushed to monopolize social life, crowding out needed social diversity rather than empowering real community self-determination. People are deeply confused about what they want from the state, and we can unravel some of the confusion by thinking about two registers of belonging. The first we could call the sublime register, where the state appears to offer group membership in something highly abstract and impressive, something that at the very least carries the hints or undertones of religion. In the second register, the real or functional one, there is actual community belonging, which only takes place at the level of the local and tangible. In a sense, real community just is co-presence, trust, reciprocal obligations, and mutual aid. It is not possible to get this from the modern state, which was not designed for community, but for something close to its opposite. While the state can never provide the intimacy of a true, local community, its impersonality is part of its appeal. Its very remoteness allows for idealization, projection, and the sense that one’s community is connected to a vast, meaningful order—even if that order is largely abstract or constructed. People are drawn to power stable enough to endure beyond their own lifespan, to symbols seen as above the everyday, and to the comforting nonsense that their identity is part of something timeless.

Were we to adopt a broader historical perspective, the contemporary obsession with the nation-state would appear odd and even quasi-religious in its fervor, symbolism, and misplaced emotional investment. In the modern era, much of the religious energy and attention once poured into the church is now directed at the state, very often in ways remarkably similar structurally and tonally to formal religion. We should not understate the importance of the psychological mechanism: whereas organizing and helping to provide needed services within your local community, outside of official channels, is regarded as radical or fringe, perhaps even dangerous or subversive, meaningless voting and politician-worship is strongly socially validated, zero-risk or friction, supported by your school or workplace, etc. The concept of displacement can tell us much of why we end up with a politics of empty spectacle and Two Minutes Hate-style rage-venting. In the realm of political power, there is a constantly accumulating, pent-up psychological energy or stress, where we are unable to touch or address the real object of power, which is remote and forbidden. Elections and voting are a way to redirect that energy to something that can be played with safely by children (we are the children to the ruling class), a venting ritual that allows us to feel we’ve participated in politics even as we clearly can’t confront the structures of domination directly. It really is remarkable how infrequently we discuss the psychological functions of extremely remote power, the worship of which seems to be something close to necessary to the core subjectivity of the modern person. People like the state because it, again like religion, picks them up out of the here and now and into the everlasting. Its abstract nature gives it the ability to take on the role of a sacred point of reference. “Of course we must have a government.” And when you hear it, there is no hint of embarrassment, no thought of what it might mean if that were true. Its distance gives the state its aura of legitimacy; it is “imagined and experienced as a permanent, trans-historical fixture structuring public power and authority” and thus safe, orderly, protective. Its distance is part of what allows people to make total fools of themselves in seeing the state as something socially helpful. The system of mass culture takes potentially meaningful cultural and social forms and turns them into commodities and spectacles, orienting subjectivity toward empty, anxious consumption rather than real critique.

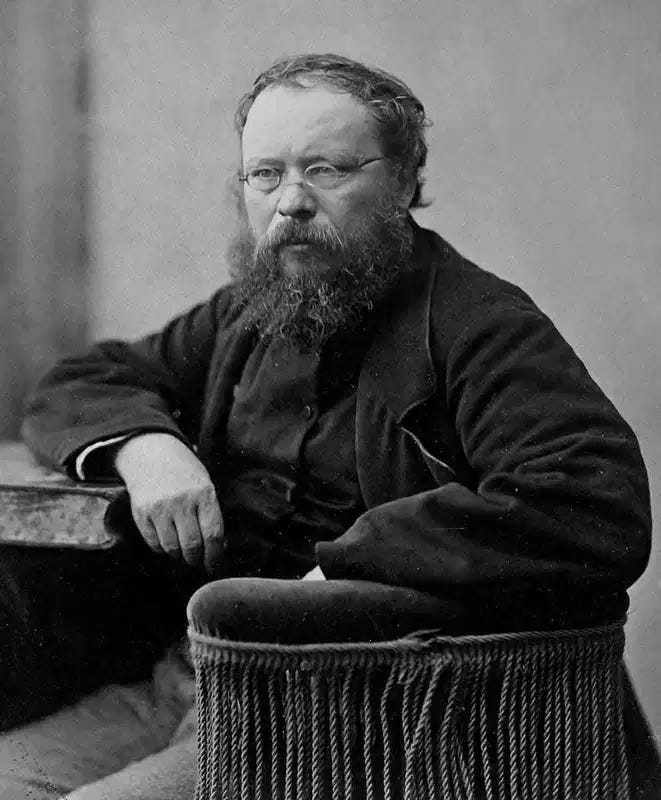

What we are missing today are the intermediate social spaces, the spaces between the isolated individual and the state or institutional capital. Genuine community is impossible without these key intermediate spaces. These are the local groups, sometimes civic or religious, sometimes informal, that enable true, ground-level dialogue, fostering trust and enable collective struggle. They offer a structural and relational paradigm that comes from within the community, rather than governing it for its own advantage from the outside. Today, many of our discrete problems fall into a broad bucket defined by our inability to effectively watch the watchers, to get out from under a fundamentally criminal government. Anarchists, localists, and decentralists have emphasized the importance of intermediate social spaces, in which free individuals come together to self-manage their own affairs rather than surrendering autonomy and control to either governments or capital. Their work points us toward ways of organizing social and economic life that restore trust and accountability by multiplying centers of oversight and aligning incentives with the happiness and wellbeing of the community. For Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and generations of anarchists, such intermediate spaces are the lifeblood of the liberatory movement and the testing grounds for and schools of horizontal self-government. The cooperative, the mutual aid society, the guild – these are the sites of learning to take responsibility and power back from the state and capital and to develop solidarity and common understanding. One may be reminded of Errico Malatesta remarking on “the alleged incapacity of the people” by insisting, “Only freedom or the struggle for freedom can be the school for freedom.” The crisis of today isn’t so different from the one Proudhon identified, the state and the capital systematically attacking and eroding society’s intermediate bodies, with individuals isolated and exposed to domination and exploitation. Free association and mutual aid, genuine participation and community, these thrive in the regions of life between the isolated individual and the centralized institution, between the authoritarian state and the exploitative, alienating capitalist market. In rejecting both state and market monopolisms, decentralized systems multiply centers of oversight, align economic incentives with the wellbeing of the community, and encourage a diverse array of governance and resource management models to coexist and federate together.

The interesting point of convergence between the various decentralist traditions is the insistence that large-scale structures emerge from, and can only be made healthy and vibrant through, local practices and local vitality. This insight brings a dose of humility to those interested in general theories of the state and capital, spotlighting the generative substrate of the small and everyday. Because commons-based cooperative models of social and resource organization outperform on resilience, long-term stability, participation, and participant satisfaction, the socialist left should invest in building out and federating these systems, never in trying to capture the authoritarian state. This is not a kind of political quietism. It is an active and material attempt to replace brutal and extractive relations with community-level, user-owned organizations. But it does require a denunciation of political power and a recognition of the fact that genuine freedom is not in the winning of the state, but in bypassing it, acting today as if you are already free and self-governing with your neighbors. If we say we want to cultivate cooperative, horizontal relations, to have a system that isn’t hierarchical, then why are we trying to reproduce authoritarian hierarchies through the state? Fundamentally, we can’t be interested in taking over the state or we’ll remain lost in a pattern of reproducing anti-social, authoritarian governments. If your movement does succeed in taking over the state, they will find that it is not a thing to be taken over at all. They will find themselves its servants. “The Marxists did not capture the State, the State captured them.” At this point, cultish fixation on state power is contrary to the worthy goal of building autonomous counter-power within our neighborhoods, serving concrete, material needs without waiting for formal authorities or permission. As Alex Prichard writes:

First that the normative force of law is undermined by the institutions which defend it, and secondly that it imposes and entrenches social conflict in the interests of those who define that order, who cannot ever truly be the working class governing itself, for as long as it does so through minority and relatively autonomous institutions like the state. In other words, from an anarchist point of view, the centralisation of the state and the institution of sovereignty are the problem, not the solution. This fact was not fully appreciated by Marx and Marxists, except by those dissenters who lost their heads for their efforts (this list is too long to put in parentheses. For a good discussion, see Van Der Walt, 2011).

Ultimately, Marx was wrong about something important – indeed, about what is arguably the most important social question of all, in his belief that the state should wither away after class antagonisms have been banished forever. Because class antagonisms are clearly embedded in the very relations that make up the state, the state needs to go before we can have a free, classless society. We don’t have another option anyway; the institutions are crumbling as we speak. Decentralized, non-state forms of organization directly embody the principles of liberty, equality, mutuality, and solidarity, and they do so without mediation by a central authority. In the place of utopian abstractions (which perhaps aren’t without their merits in fairness), we have tested and proven systems of self-provisioning and governance, offering a level of stability and social trust, to contrast with the dispossession, forced precarity, and socially disconnectedness and alienation.

The work of Nobel Prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom (1933-2012) perhaps offers an alternative to the superficial connection between concepts of stewardship and a stakeholder society and the political right; she explores how these ideas naturally flourish in cooperative and communal local economies, without necessarily undermining the idea of an individual right to own property. Her trailblazing research approach showed from the field that bottom-up, community-driven governance at the local level has certain advantages recommending it to highly bureaucratic, top-down directives for the fair and sustainable management of shared resources (e.g., fish, timber, irrigation and water management systems). Top-down commands short-circuit the processes of experimentation that must attempt to sort through the specific, local variables that present themselves on the ground:

Ostrom recognized that communities collectively depending on a given resource are more than capable of designing their own practices for use and access, administration and management, conflict resolution, change management, etc. The rules the local community provides for itself will better fit local conditions and will be more readily adaptable, incorporating specific, local information and feedback more easily and effectively than authoritarian, one-size-fits-all approaches pushed from the state and capital. Mechanisms of accountability and trust also unsurprisingly function more smoothly at the local level, as resource users share in the responsibility for ensuring that all participating are ethical and accountable. Those charged with regulating the system are members of the group who actually use and shepherd the resource, so the system of monitoring is not a foreign or alienated one, imposed by some faraway ruler, but is part of the internal logic of a system of local attention and care. Ostrom stressed the unique advantages of polycentric, community-based management of shared local resources, demonstrating that collectively managed commons can help us avoid the inefficiencies and moral hazards associated with capitalist and government forms, both examples of coercive monopolism. Political scientist Rick K. Wilson explains Ostrom’s ideas on what makes local norms thrive:

[C]onditional cooperation is common. Much of conditional cooperation is built on beliefs about others and whether they will contribute to the public goods. Ostrom argued that conditional cooperation was central for understanding the resilience of norms. Pure cooperators would be quickly taken advantage of by pure free-riders. However, with a population mix of free-riders, pure cooperators and conditional cooperators, contributions to the public good can thrive. Much of the recent research reviewed by Chaudhuri points to mechanisms by which beliefs can be sustained and by which individuals can act strategically to ensure cooperation.

Ostrom’s insights about conditional cooperation are important, and we’ve all seen this phenomenon in action at one time or another: in a group activity or a social setting, there is often an initial reticence or hesitation, perhaps stemming from embarrassment or from uncertainty within the group as to how others will behave. For many, waiting for others in the group to make the first move is simply natural prudence or caution kicking in. Often if we see others take the initiative and jump into the action, we're sufficiently emboldened to follow suit, touching off a cascade of cooperative or at least synchronous social behavior. Studies have confirmed that when we see others volunteering to participate or take the lead, we’re more likely to contribute to a collective effort, hinting at the untapped social potential of genuine trust and solidarity. When others participate voluntarily, we take this as a visible signal of at least a modicum of safety and a shared commitment to whatever project has been joined, reducing the fear of danger or exploitation, offering the first overture in a dialogue of ongoing mutual assurances. Such relations are fundamentally different from the orders of a state agent or a boss. Genuine trust and cooperation, because they are what people actually want, spread quickly after a critical threshold is reached, which is why the state and capital invest so heavily in keeping us alienated from ourselves and each other. They know there would be a cascade of positive, liberatory social action if we got together and moved out of initial hesitation into participation and change.

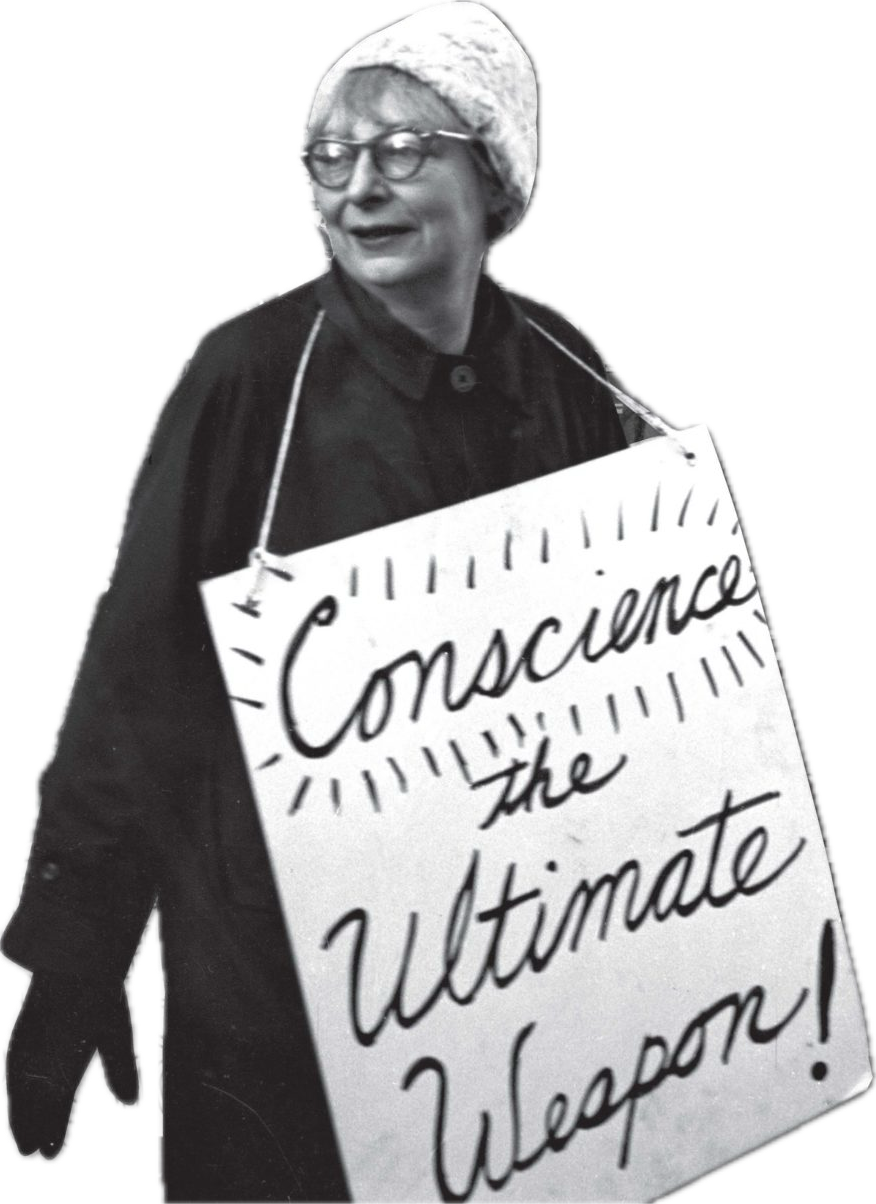

Another fierce critic of top-down planning, Jane Jacobs (1916-2006), saw the city as a complex ecosystem, a world of change and unique interconnections rather than a rigid mechanism operable from above or from the outside. From this picture of the social environment, Jacobs believed that for development to be appropriate and sustainable, it would have to be heterogeneous and growing naturally from the bottom up. Her work continues to offer a number of valuable insights on the importance of the livable scale. She articulated a vision of human-scale urban design emphasizing factors like building height and the resident’s proximity to diverse walkable areas. She believed that creating the sense of an enclosed street-scape, intimate though inviting and vibrant, would ultimately create safer and more tightly-knit communities, that is, neighbors who treat each other as such. In centering the need for a durable connection between people and their local environment, Jacobs also offers potential answers to the alienation so frequently produced by today’s American environments. Characteristic of Jacobs’ work is her emphasis not on abstract political theory, but on frameworks of trust within informal social networks, which she saw as the real fabric of social and civic life. She believed healthy communities would have their “eyes on the streets,” naturally minding and tending to their own affairs, providing for their own safety. These are forms of transparency and informal social monitoring that can only arise in coherent small-scale communities where there are high levels of trust. Jacobs’ idea of open, mixed-use urban environment encourages a culture of active and open public life. This is, no doubt, part of what is sorely needed today: public life that’s truly open and free (in the sense of having an admission price of $0 and the more philosophical meanings). Jacobs envisioned streets as lively and festive, creating a shared, free space for cultural exchange and belonging. Places designed for people (rather than car traffic) promote the neighborly interactions that are the life of local business and community happiness and cohesion. If a community is going to be healthy, it will ultimately be because it has a strong bottom-up, anti-authoritarian ethos and insists upon governing itself, with which attitudes must also come a culture of neighborly sharing and mutual aid.

Kirkpatrick Sale has argued for decades that societies should consciously and deliberately decentralize everything from capital ownership and productive and trade activity to government and social life, reestablishing robust and resilient communities, strong enough to meet people’s material needs. He argues that the collection of power in large, distant bureaucracies and corporations leads as a matter of course to vast inequalities, with oppression and resource extraction mirroring those of colonial relationships, whether the victims are in the global south or in marginalized communities within the rich countries. Because this extractive logic is embedded in the structure of the political and economic system, it is at the core of how citizens are treated, that is, as resources to be managed and mined. This helps to explain the failure of efforts to reform this system from within it, which often end up reinforcing and recreating the same age-old patterns of domination and extraction. We aren’t going to get any genuine change in the direction of a free society until we begin to understand that the problems we see have a structural character, and therefore can’t be reduced to some people being good and others being bad. Until we govern ourselves directly and polycentrically, nurturing autonomous, intermediate social bodies, the structural logic of the state and capital will continue to dominate us. And it will continue to extract from us just as it has extracted historically from the global south. The logic is the same; only the degree of exploitation is different.

Sale’s thought affirms decentralism as the essential framework and guiding principle for the realization of freedom and ecological health and sustainability in our time. He argues that the crises of modern civilization, from corrupt and authoritarian government and inequality to environmental degradation, are first and foremost the inevitable result of “bigness grown out of control,” the concentration of decision-making power and wealth in ever-larger governments, corporations, and institutional systems far beyond the manageable human scale. Central to his thesis is the conviction that truly democratic systems require social and political units sufficiently small to permit meaningful participation and strong local control, where citizens directly influence the processes and decisions that affect their lives. Decentralized, human-scale communities foster real liberty by ensuring autonomy, self-sufficiency, and protection from coercive, centralized authorities, whether state or corporate. Ecological sustainability further depends on the capacity of local communities to steward their own resources, adopt appropriate technologies, and develop practices attuned to the needs and limits of their specific bioregions. Sale emphasizes that bringing institutions—whether governments, businesses, or physical infrastructure—back to human scale is a prerequisite to a just and sustainable society. This process involves not only the devolution of power and the dismantling of overgrown systems, but also the active creation of a dense network of resilient, self-governing localities. In his words, “the eternal, resurgent, inevitable power of decentralism” must prevail for the well-being of people and planet alike; decentralism is not just a philosophical preference, but a necessary framework for survival, prosperity, and genuine democratic self-governance.

From such decentralist thinkers, we have flexible social models that actually want to leverage the underutilized capacities of local communities. Local norms and practices are more flexible and sustainable, but they’re also more legitimate to the people who are being governed, because they’re transparent and the people involved are genuine stakeholders. When federated across a region or regions, these institutions could coordinate beyond the local without falling into the monopolism of the state or capital. Decentralized systems could nest upward to address larger issues as necessary. It is not at all clear, contrary to the arrogant claims of elitists and authoritarians of all kinds, that the centralized state form is necessary to allow for scaling certain kinds of expansive projects or policies. Federalism plausibly allows for as large-scale a project as is possible for any system; it only demands that such a project is sufficiently meritorious that it compels the broad cooperation of a large group of autonomous stakeholders. Such stakeholders could be workers’ groups and guilds, local communities, land trusts, and countless other forms of non-hierarchical, anti-authoritarian methods of managing the fact that a real community is about what is shared. Statists are always telling on themselves and here it is no different: they are admitting that actually convincing stakeholders of the merits of their vision is not all that interesting to them. They would prefer to use plain, old-fashioned violence, calling it law and police, of course, believing that they must know better and that anything small or local deserves to be and should be steamrolled.

Dave, you really unpacked a lot of good information and insight in this article!

Keep them coming!