It is almost axiomatic in political philosophy that a stable and enduring social order requires the state, a powerful ultimate authority, exclusive within a given territory, to which all other social institutions must be subordinated. Across the ideological landscape, it is largely taken for granted that the division of power within a single territory opens the way to social confusion, disorder, and violence. The state, the leviathan, is the necessary paternal figure, endowed with the power to make the rest of the social order fall in line under a uniform set of standards imposed from on high.

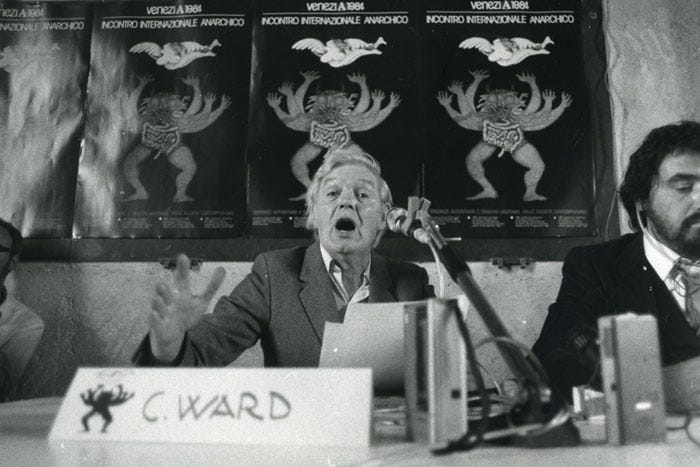

But what if roughly the opposite is true—if social vitality, cohesion, and accountability thrive best in an environment decidedly without a final arbiter, a court of last resort, or a top boss who can dispose of all questions for us? There have always been decentralists who believe that dynamic stability is achieved through the multiplication of effective social orders, through federations of small, flat, autonomous organizations. The decentralist tradition suggests that both the modern state and the formal capitalist market have absorbed and colonized, if you will, far too many functions and too much power previously held in society. Yet there is a clear sense in which the “small is beautiful” banner opposes the spirit of our age. Today, the political sphere is dominated by the proponents of colossal size, despite any gestures to the contrary. Growth is progress, progress growth. Much of the political left facilely equates the building of the public, civic sphere with the expansion and empowerment of the state. The prolific anarchist writer Colin Ward (1924-2010) said the opposite, contending that “the weakening of the state” and the development of its imperfections and contradictions is a social good and a survival necessity. Only by draining power away from the state can we build other loyalties and centers of power, developing “different modes of human behaviour.” Ward was influenced by the decentralist politics of Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921), who argued that socialism could never be squared with “State bureaucracy and centralization” and “must become more popular, more communalistic, and less dependent upon indirect government through elected representatives. It must become more self-governing.”

Following Kropotkin, Ward advanced what he called “topless federations,” seeing that it is the small group at the top of the pyramid that stands in the way of accountability and the administration of justice. We are trained to believe roughly the opposite of the truth that Ward noticed, instructed to treat those at the top as our betters, specially endowed with the power and wisdom to rule. Ward and other anarchists have argued that rather than being a description of reality, the received philosophical defenses of the ubiquitous pyramidal structure are more accurately reckoned as after-the-fact rationalizations of oppressive authority.

For Ward, “the whole pyramid of hierarchical authority, which has been built up in industry as in every other sphere of life, is a giant confidence trick by which generations of workers have been coerced in the first instance, hoodwinked in the second, and finally brainwashed into accepting.” Whereas we have been taught that large scale and towering gradations of rank are necessary to the achievement of certain efficiencies and outcomes, we have paid far too little attention to the “fantastic inefficiency of any hierarchical organisation.”

The inefficiencies associated with the large, pyramidal institution owe chiefly to the fact that its leaders are cut off from “the knowledge and wisdom of the people at the bottom of the pyramid,” the people running the organization despite the incompetence and rent-seeking of its leaders. Ward also points out that there are inefficiencies owing to the fact that the capitalist economy does not permit people to choose their own projects and tasks. An organization cannot perform optimally when workers are motivated by compulsion and fear rather than any meaningful identification with the work itself. Anarchists like Ward have argued compellingly that “given a common need, a collection of people will, by trial and error, by improvisation and experiment, evolve order out of the situation,” and that such spontaneous order will better address the needs of the group than rules arbitrarily imposed from without. Ward took care to point out that anarchists “are not concerned with recommending geographical isolation,” and explicitly argue for social systems that are open and connected. The anarchist conception of federalism does not contemplate a confederation of states, but a complex web of civic and economic organizations agreeing for particular purposes, each one maintaining its independent identity and agency.

Today’s cultural elite, regardless of political affiliation, wrongly supposes that the brain of the system is to be found there at the top of the pyramid. But the brain is in fact distributed throughout the system, with the largest part of it located at or around the base of the pyramid, where most of the people (and thus brainpower) are. Large and hierarchical institutions are quite literally pinheaded, blindly following the orders of a handful of leaders detached from most of the knowledge, experience, and cognitive power. Today’s organizations are defined by the fact that there is a small group who “makes decisions, exercises control, limits choices, while the great majority have to accept these decisions, submit to this control and act within the limits of these externally imposed choices.” It is no wonder that such institutions are incredibly inefficient at producing anything but violent conflict and social immiseration. They can’t help but do this because their very purpose is to separate people, through nested hierarchies, from any control over their time or their work.

The ideological hegemony of the state in political thought is not unlike that of global capitalism in economic thought—this is the system to which every country on earth must submit. Even its apparent rivals share its most fundamental structural features—towering scale, command-and-control hierarchies, few powerful rent-seeking executives at the top, ranks of exploited workers at the base. It should not surprise us that in the era of global monopoly capitalism, as multinational corporations have grown to astonishing sizes, inequalities have grown with them. An incredibly small and ever-shrinking group of people now own and control almost all of the world’s wealth—not because they’ve bested the rest of us in some imagined free market, but because they have sidled up to state power and grabbed ahold of it. An Oxfam paper published earlier this year, “Takers Not Makers: The unjust poverty and unearned wealth of colonialism,” sheds welcome light on a worsening crisis of global inequality, showing that billionaire wealth has skyrocketed, rising three times faster in 2024 (which saw an overall increase of $2 trillion) than it did in 2023. The report finds that the global colonial system “still extracts wealth from the Global South to the super-rich 1% in the Global North at a rate of US$30 million an hour.” The report adds that no less than 60% of billionaire wealth comes from inheritance, cronyism and corruption, or monopoly power, a figure that is surely low and does not account for key sources of state-granted corporate privilege (e.g., intellectual property).

We are witnessing inequalities such as history has never seen. Adam K. Webb describes a kind of “social monism,” under which social authority has increasingly collected in and “centered on modern higher education,” churning out corporate automatons with a “common socialization to staff these overbearing institutions of late modernity.” Webb argues that given this homogenized social authority, “this is, in many ways, one of the most hierarchical periods in human history.” He addresses the question of how we “disaggregate power again, unbundle sovereignty, return power to society, and diversify social life.” Echoing many decentralists, Webb advances the cases for a more pluralistic legal framework that resists the monopolies of both state and corporate interests, ensuring that the legal system remains a thoroughly public domain, rather than a mere procedure for ratifying those interests. The suggestion that there is not a single uniform social and economic system that will work at all times, places, and scales is treated as apostasy. Yet it is so clear that every place has its own traditions and rhythm of life, its own customs and vernacular, and that these are inseparable from cultural attitudes on what works for people. Humans seem to need the place-bound, to seek out local community and cherish what makes it special. Introducing a 1989 interview with Leopold Kohr, Canadian writer and broadcaster David Cayley said:

Kohr’s thought rests on the idea that nature, including our own human nature, must finally be our guide. The scale on which we can happily live is given by our own embodied being. It is the scale of feet and hands and eyes, the scale of what we can see and touch, and walk towards. It is the scale of beauty, which must always recognizably reflect our own proportions. Beyond this scale, we quite literally take leave of our senses and arrive at something which is ultimately monstrous and inhuman.

The tendency to seek smallness appears to be an aspect of humanity that cuts clean across cultural lines. Ward described the experience of the Dinka people, who “explain their cellular sub-division with such phrases as ‘It became too big, so it separated.’” In societies that do not share our modern obsessions with special ranks, titles, and “expertise,” which confer on their few holders special power over everyone else, competition between local, autonomous groups maintains balance and a high degree of order. “Harmony results not from unity but from complexity.” People will naturally seek to subdivide giant monolithic organizations, to carve out discrete units of smaller and more manageable size, defined by shared values, interests, and goals. The historical role of the state has been to prevent this socially beneficial breaking apart, precluding and stamping out the small-group autonomy and agency that forever reassert themselves among groups of people. The forcible separation of people from their own affairs requires these constant interventions to reconsolidate resources and decision-making authority. Your small band cannot be allowed to govern itself, but must align with uniform standards, imposed by a boss from outside, from above. Far from being natural and inevitable, hierarchy must always be tended to through violence and coercion.

The massive, top-heavy organizations of the present day are balanced only precariously, viable due to massive state support and periodical bailouts, both valued in the many trillions of dollars. Here, an analogy to geometry helps to clarify the fundamental problem: according to the square-cube law, the weight of a thing increases much faster than its strength. The structural integrity of the unit is compromised as it grows larger, the scaffolding bearing more weight and pressure. The skeleton must be reinforced with increasing frequency and vigor. We witness this all the time, all around us: strikes must be broken, dissent crushed, votes suppressed, voices silenced.

Physical principles, too, offer useful analogies and insights: smaller structures will tend to have higher frequencies, with lower masses and higher levels of rigidity. This means that they are more durable against lower (that is, larger scale) resonant vibrations. A tall skyscraper must sway enough to absorb the forces of the wind, but not so much that structural integrity or occupant comfort are affected. Thus, in physical terms, we may see the dedication to smallness as a mechanism for allowing perturbations in the system to oscillate without growing out of control in a way that would threaten the viability of the system at large. The higher you go, the more difficult this is, and at a certain point, to go further is folly. This is no less true for our social structure and its institutions, and we have reached the summit of folly.

Technology might have made society more decentralized, and it still could. Many social theorists from a range of academic and philosophical disciplines (e.g., Leopold Kohr, E.F. Schumacher, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Benjamin Tucker, Ralph Borsodi, Peter Kropotkin, and many others) predicted that new technologies would empower smaller-scale groups and social systems against the power of the authoritarian state and global monopolies. If that vision is not still within reach, if our own tools cannot be called upon to empower the small and local rather than enriching the few, then perhaps they are not tools worth having. We can decide how to use technology and—no less important—who owns it.

We can no longer afford to pretend that the quality of a system of human government is scale independent. We have deluded ourselves that appropriate public policy can be dictated from a great distance and from great heights, imposed on people with diverse and varied needs, values, and circumstances. The essence of the massive-scale institutions of the present is that we are alien to them and they to us. Perhaps the most important rationale for decentralization is the relocation of political and economic power to a proximity such as to make it susceptible to democratic control.

Nice read!